Interviews

Publishing Into That Mystery: An Interview with Eileen Myles

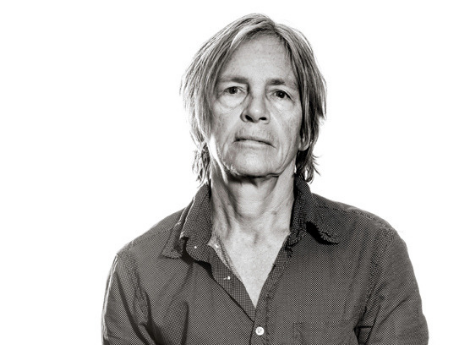

Called "one of the essential voices in American poetry" by the New York Times, and "one of the savviest and most restless intellects in contemporary literature" by Dennis Cooper, Myles has published numerous lauded books and previously exhibited photography at the Schoolhouse Gallery in Provincetown. Their Instagram is @eileen.myles. Also on view at Bridget Donahue is The Theme Is Green, described by Myles as "a big beautiful show" of paintings by Monique Mouton.

Eileen Myles, poems, November 11, 2018 - January 16, 2019,

* * *

How does putting your photography out into the world, via Instagram and your show at Bridget Donahue, feel different than publishing books of poetry and prose and giving readings?

It just remains. When you read a poem there's a tone afterwards. Having a photo on the wall or even on IG has more that quality. Like the photo and the after effect are all the same thing. I'm more aware of the parts of poetry and that something else is coming. Like there's just a condition of presence to photographs. A reading might create a present feeling but that's not what poems are doing though it might be what they're thinking about.

What makes Bridget Donahue a good fit for your work?

I love the big long space, the raw floor. It reminds me of an earlier Soho and Tribeca. These were personal spaces. There was kind of a kunsthall type space in the 90s called Threadwaxing space and it reminds me of that. And Bridget's really open and precise. I count her among the great curators I've met – I think of Pat Hearn and Lia Gangitano at Participant. Bridget just exudes confidence and matter of factness and she shows great work so I was unsurprisingly thrilled that they would show my photos. It's a wide smart context. Erin Leland who works for Bridget is stellar. Those guys are beyond feminism. Bridget Donahue's sort of rangey. Not precious. I'm a serious amateur but I know about art. I'm not kidding when I call them "poems."

You've discussed in various interviews that a poem can feel especially alive when you read it to an audience, and that it transmits a different kind of power on the page. Do you see distinctions between the energy of a photo in the moment you post it (and perhaps in the hour or so after, as likes accumulate), and that same image's energy once it's deeper in the archive of your posts? Once it's printed and displayed in a gallery?

Yes. I can't help feeling that a photo is hotter at some points. It came out of a moment and there's something collective about that. I mean in light of the moment of posting on IG. How close is your moment to my moment. I'm almost superstitious about the secrets of that act. It's almost like when you publish a book you don't know whose it is. You publish into that mystery. To be able to relay that greenness is alarmingly hot to me. I'm always stumbling with some kind of aloneness in the world too. I don't feel ashamed of it but to lift the lid on your existence in a way like we do in poems but to then hand the setting or a quirk of landscape to an accidental number of people seems like what it really means to live in our time. Even a little holy. We have this communion that can really suck or not.

How did you go about selecting 20 photos to include in the show? You've posted over 6,000 on Instagram. Were there any images that you knew had to be included? Any that felt unexpectedly essential but weren't obvious first picks for you? Any that you feel especially close to?

I'm shocked it's that many. Well I wanted them to be fairly recent. And at least what's on the wall is from this year and last year. There's a purple drink and I felt like that was the color of the show. And there had to be an apartment shot because I'm devoted to showing my home as a studio.

I'm crazy about the red-legged table and it truly reminded me of CA Conrad's line "the world spinning on its one good leg" which is what I drew the title from. Some of them just feel like drawing. The ice cream was a latecomer and everybody else's favorite. I was like really. When I posted it I liked it but it had a way of fitting for everyone else almost more than me that was fascinating. I had a few friends I was showing my choices to. Nobody could understand the dude typing poems on the street. He's like a sight gag for me. I'd hate the feeling that every image was "special." I wanted it to be sorts of things and there be like a conversation going on.

If a viewer walks left to the right, the first photo they encounter on the wall is I told him I was a famous poet and he never heard of me., a full frontal view of that dude you mention, seated at a typewriter on the sidewalk. This is the only photo on the gallery wall in which you can see a person's full face (apart from irish baby, a photo of a framed photo of a baby). Can you give insight into why it's first in the series, and how other images fell into their places?

He is kind of leading out into the world. Like a passerby except I was the passerby. He is too where poetry and photo meet. It's almost like leaving that at the door. Okay we did that. And I become more anonymous in that exchange. Some things (I mean photos) seems more transparent and others heavy. I didn't want it to get clogged. The shapes are important too like relative emptiness and then a line. The belt from the bathrobe talking to Honey's long foregrounded leash. I like her on the opposite end. Again some wit – a dog sniffing somebody's boxers. Attachment. It's serious and funny. I protected the breast I thought and put it inside.

In your artist statement you write, "In 2014 I had an open fall & had by accident adopted an orange pitbull. I had rescued her from the jaws of death & now I must walk her. She nearly yanked my sixty-something arms out of their sockets & together we explored what lower Manhattan had become. The bliss of geometry, trash: instantaneous configurations, Honey's utter curiosity & openness to day & evening all led me to putting IG on my phone & exporting our nights & moments." Honey appears in two of photos in this show, looking tender (in Consternation about Mimm's, she's far away and blurry, looking up at you, connected to you by her leash, and in I think Honey missing Joe, her nose is buried in boxers). Your photo line seems like it could have been taken from her eye level. Can you elaborate on Honey's presence in these images, the ways her power and personality lives in and around them?

Well the uncanniness of a relationship with an animal is that there's so much communication without language. Photography seems leveling because some real part of what she means, or how she means comes straight at you. Mimm's is a ranch that very suddenly stopped letting us (or anybody) walk there. We hit a wall that day by getting there and suddenly it was ne plus ultra. It was just like a loud sound. The distance was not being able to tell her. Photos sometimes are simply souvenirs of speechless moments. And for Honey her being stuck with my equally useless mastery. I swear she knows how beautiful she is. There's something about her that is posing. Is comfortable with being seen. Deeply open.

Are all of the titles of the photos on view the original Instagram captions, and were those that are titled " -" originally posted without captions? How does titling images feel different from titling poems?

Yeah the untitled are untitled. I was taking a risk with being gabby. irish baby feels perfect. So does the typewriter guy, it kind of makes it. But other ones are sort of babbling and I'm being sort of documentary about it like keeping to the original not cause it's great but more like a signature of the moment. Titling poems are more progressive. They usually come with a poem but I often change them. I like to get the title right or at least not make you think about it unless it just came and surprised me and I'm as helpless as any reader.

irish baby is frank, slanted, free. Given its composition, it's almost as if your phone was tossed in the air and caught this image on its way up. Your writing often emits a briskness and buoyancy as well. The first piece in your new book Evolution, "[I am Ann Lee]" (a talk you gave at a conference in June 2017, The Feminine Mystic), feels like a wildfire – the whole thing is bright and fast and touches everywhere (your mother, Comey, sheep, Édouard Glissant's Utopia, Thanksgiving, a blue stone . . .). How do you see speed – these various kinds of leaps and flashes – operating in the content and composition of your photos, and in the practice of taking and posting them?

Well the phone is marvelous. You can be picking it up and see an accidental picture. I love those. But the world heaves towards the phone sort of. I think the red table leg was an accident like that. The apartment window is slow and solid. There is that. That times are so different. Like things are made out of time, fleeting or compressed and you want to put them together. The very frame of photography itself is pretty funny. You're captured by the world and then you capture it. I suppose what I love about using the phone to make pictures is that what's implied always is movement. I mean even the apartment is the movement of time, slow accrued time. 41 years in a place, with a view. It's like owning the sentimental and saying it's monumental. Lightening the aghast.

Can you give insight into your decision to include"earlier works", a plywood box of six framed prints from 2015 – 2017? Looking through it feels like flipping through prints in a frame store or paintings in a bin at an artist's street stand. At first glance, viewers may see the top half of your 2016 untitled photo of a painting, which gives off the impression that the bin includes framed paintings, rather than photos. What made you place these particular works in a box instead of on the wall?

Well I did have a past with exhibiting things in Provincetown. And I had only just started to think about frames which I think is a big deal for some photographers. So once I decided to pin these ones to the wall and skip the framing step it seemed funny to put a selection of earlier framed ones from the first shows in a bin to almost devalue the formal and elevate the casual. I had even thought about making them cost less but we abandoned that. I don't truly feel that way though about what's inside the frames. Just the presentation, I wanted to mess with that. And that selection really felt generic in that I wasn't trying to express a relation between them. Dennis [Cooper] and Kevin [Killian] being poets, Nicole [Eisenman's] painting, the little things in the picture window in LA, they feel really stray the way posters in a bin might. But they are favorites too. Akilah Oliver is in there in complete seriousness but maybe not front-loaded like she would be on the wall.

Do you see your photos as part of a dialogue with any other Instagram users or visual artists in particular? What Instagram feeds do you love/would you recommend following?

I like Richard Tinkler's paintings that he constantly posts, same with Robin Bruch, Kathy Bradford. All those accounts are just their names. And of course Linda Sarsour, that's @lsarsour. People who I like come and go. People stop posting or their mode changes.

I imagine you take photos you don't post on your Instagram, and these accumulate on your phone. What makes you decide to share a particular photo with followers, rather than saving it without sharing it, or sharing it with just a friend or two over text?

I took pictures when my mother was dying, even of her dead body. I didn't want to put any part of that passage in public. Parts of my personal life too of course. I take more selfies than I post. I'm cautious with them because you take selfies for all kinds of reasons and that process isn't necessarily public. It's like looking in the bathroom mirror, for one. Though sometimes that's great.

* * *

Eileen Myles was born in Cambridge MA in 1949 and came to New York in 1974 to be a poet. They are also a novelist, and art journalist, have written plays and libretti and most recently adapted Chelsea Girls into a screenplay. Their twenty-one books include Evolution (poems), Afterglow (a dog memoir), a 2017 re-issue of Cool for You and I Must Be Living Twice/new and selected poems, and Chelsea Girls. They are the recipient of a Guggenheim Fellowship, an Andy Warhol/Creative Capital Arts Writers grant, four Lambda Book Awards, and the Shelley Prize from the Poetry Society of America. In 2016, Myles received a Creative Capital nonfiction grant and the Clark Prize for excellence in art writing. They live in Marfa TX and New York.

More Interviews

To Keep It All from Vanishing: An Interview with Timothy Donnelly

As for form, I’ve always been interested in patterning of all kinds, probably for a lot of reasons. I can’t account for every one of them, but on a primal level, underneath them all, as far as poems go, I’ve always felt that poetry’s ancient emphasis on the physical properties of language, and the use of certain of these properties (such as quantity or syllable count or stress) as leading principles in its composition, is what most distinguishes poetry from other kinds of writing, and what makes it most palpable, most present.

Read Article