Poems & Essays

Old School

Poets on poets and poems from the past.

On John Keats’s “This living hand”

I was just starting out when I stumbled upon John Keats's last serious gesture in poetry, the final fragment, a terminal point. I felt the blood in his hand, the trauma of what could never be finished, the lure of the partially whole, and it has reminded me ever since that poetry is a bloody art. It's a form of play, true, but the stakes are mortal. Everything is on the line.

Continue ReadingMore Articles

On George Oppen’s “Of Being Numerous”

I was 23 and self-effacing, my hair in a tight bun, when I read these lines, out of George Oppen's Of Being Numerous. I read them on my hour or so ride on the Q train, when I went to teach Brighton Beach community college students who had failed their basic reading and writing exam. That season, in which one of my students left obscene phrases on torn pieces of paper on my desk, I tried to teach poetry to him and the others and sometimes succeeded.

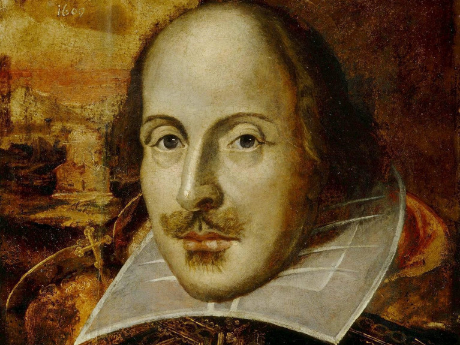

On Shakespeare’s “Shall I compare thee to a summer’s day”

Long ago as a high school sophomore, I had yet to experience "first love," or anything resembling it, so when I read the sonnet Shall I compare thee to a summer's day, it wasn't so much the romantic tone that entranced me. There was no particular girl or boy that I thought of as I read it in class. It wasn't the deft imagery either, gorgeous to be sure, but the poem's assertion of immortality in its last two lines. That was what got me.

On Christopher Marlowe’s “The Passionate Shepherd to His Love”

You love John Keats. I do too. He revolutionized the art, died young, left a lot of masterful poetry unwritten, was good-looking and tubercular: Keats!

But Christopher Marlowe left a lot of poetry unwritten too.

On “Ode to a Nightingale”

Poetry speaks to those of us who hear it across vast distances of time, culture, and personal identity. If I didn't believe this, there would be little for me that explains how a poem by an 19th century Englishman would so profoundly impact a 20th century Jamaican-American woman. I'm speaking, of course, of the well-known poem, "Ode to a Nightingale," by John Keats and, the unknown story of my 18-year old self's discovery of the same as a first-year college student in Miami in 1990—almost two centuries after Keats' had written the poem, in the spring of 1819, when he may already have sensed that he was dying.

On “Wild Nights”

I don't know how old I was when I first saw a poem of Emily Dickinson's; I was in a classroom. I learned that her punctuation had been altered and then restored. I also learned that she wore white and was in love with god.

On Emily Dickinson

Sundays this New York City cafe fills up and empties according to the bells that ring from the neighboring church; weekdays according to the cops' schedule. I come here almost every day to work alone in the company of others. These hours get me through the week; they're essential to the sense of discovery and possibility for which I long. But why choose to sit at the table with only books? I often have Beckett with me; sometimes Stevens; always Dickinson, whose familiar face I was surprised to see gazing back at me last July from the shelves of a lovely tiny bookstore in the 20th arrondissement in Paris.

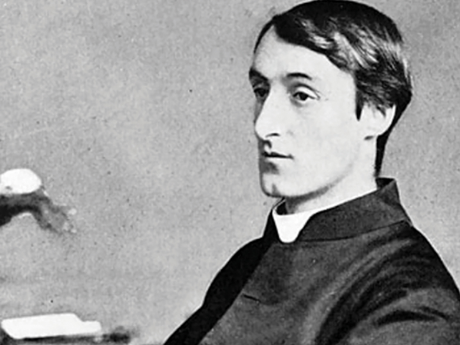

On Gerard Manley Hopkins’ “Spelt From Sibyl’s Leaves”

In our particular, peculiar time, is the end of the world ever not in the surround? We hear increasingly of the fierce consequences our environmental damage has done to the planet, the storms, wars, starvations and financial challenges that seem unlikely to abate.

On Anne Bradstreet

I have always been attracted to double-mindedness, to art that appears to think, rather than to assert. As a reader, I am suspended in ambivalence, in feeling strongly in multiple, conflicting directions. For the poets I admire, death is hideous and transcendent. God is enormous, terrifying, beautiful, and non-existent at once. This is to say that my favorite poems—and, I'd argue, most great poems—suggest minds at work on unsolvable problems. The joy of reading these poems isn't the discovery of a solution to our great anxieties and dilemmas, though they may provide comfort. Instead, they offer us the experience of listening in on an intricate mind greater than our own.