Old School

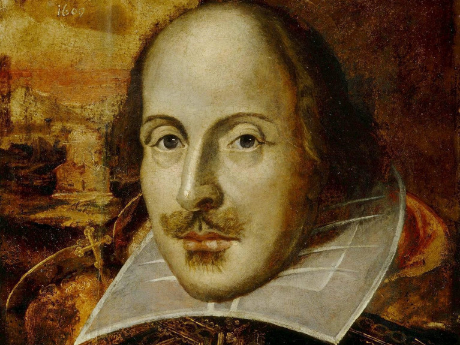

On Shakespeare’s “Shall I compare thee to a summer’s day”

Shall I compare thee to a summer’s day?

Shall I compare thee to a summer’s day?

Thou art more lovely and more temperate:

Rough winds do shake the darling buds of May,

And summer’s lease hath all too short a date;

Sometime too hot the eye of heaven shines,

And often is his gold complexion dimm'd;

And every fair from fair sometime declines,

By chance or nature’s changing course untrimm'd;

But thy eternal summer shall not fade,

Nor lose possession of that fair thou ow’st;

Nor shall death brag thou wander’st in his shade,

When in eternal lines to time thou grow’st:

So long as men can breathe or eyes can see,

So long lives this, and this gives life to thee.

Long ago as a high school sophomore, I had yet to experience "first love," or anything resembling it, so when I read the sonnet Shall I compare thee to a summer's day, it wasn't so much the romantic tone that entranced me. There was no particular girl or boy that I thought of as I read it in class. It wasn't the deft imagery either, gorgeous to be sure, but the poem's assertion of immortality in its last two lines. That was what got me.

I understood by then, of course, that literature as an art could transcend time, that it could attain something of the eternal, so long as it connected with a reader somewhere. But this poem exposed me to a literature that explicitly claimed immortality not just for itself but for its subject. And claimed it not just to the reader but to the subject itself:

So long as men can breathe or eyes can see,

So long lives this, and this gives life to thee.

The subject (woman or man?), rendered so elegantly through metaphor, is here memorialized, and through this, given value, worth. I was transfixed. My own life's experiences, as an impoverished, queer, Mexican immigrant growing up in Reagan's America, were not echoed or reflected in the culture at large—not in the media, not at church, not in the classroom. And if some aspect was echoed, like the few images in the media of men acknowledged as gay, it was under the threat or inside the wreckage of a then new and terrifying epidemic. This, unsurprisingly, made for some challenges—a life lived at the margins, a life in many ways invisible—challenges that would chip away at my sense of self-worth.

But here in this poem was a spark, a turn, a beginning. The final couplet—mournful yet celebratory, simultaneously acknowledging death and defying it. Language that could bestow worth on someone and in so doing, render him beautiful.

There would be many more beginnings in the years ahead, many more firsts, before they reached critical mass, if you will, and spurred me to write my poems—intensely personal poems, initially for sure. I write for many reasons, but the first was to call forth that which has been neglected, abandoned, forgotten, that which was never acknowledged in the first place. I write because through language I aim to create beauty from pain and ugliness, the universal always only a few line breaks from the particular. What a glorious alchemy.

More Old School

On John Keats’s “This living hand”

I was just starting out when I stumbled upon John Keats's last serious gesture in poetry, the final fragment, a terminal point. I felt the blood in his hand, the trauma of what could never be finished, the lure of the partially whole, and it has reminded me ever since that poetry is a bloody art. It's a form of play, true, but the stakes are mortal. Everything is on the line.

Read ArticleOn George Oppen’s “Of Being Numerous”

I was 23 and self-effacing, my hair in a tight bun, when I read these lines, out of George Oppen's Of Being Numerous. I read them on my hour or so ride on the Q train, when I went to teach Brighton Beach community college students who had failed their basic reading and writing exam. That season, in which one of my students left obscene phrases on torn pieces of paper on my desk, I tried to teach poetry to him and the others and sometimes succeeded.

Read Article